Yoga has been a grounding practice in my life for over 25 years. A person who finds it hard to sit alone in silence (ah, the irony of a writer who doesn’t like being alone yet needs solitude in order to create something out of nothing), moving meditation has always been the best way for me to acknowledge and know myself. I started with Ashtanga yoga, working my way through the Primary Series. I never quite “mastered” this or even attempted to move on to the Intermediate Series, instead growing bored (or frustrated, maybe both) and playing with different vinyasa, yin, hatha, kundalini, “power” yoga (which is not really yoga at all), and other types of classes. Then I would get tired of yoga and try crossfit; I’d injure myself and go back to yoga, heal my body enough to become a long-distance runner, run a marathon and then never run again, go back to yoga, become restless and start boxing, injure myself and then stop working out completely. I guess I’m what you might call a yo-yo athlete.

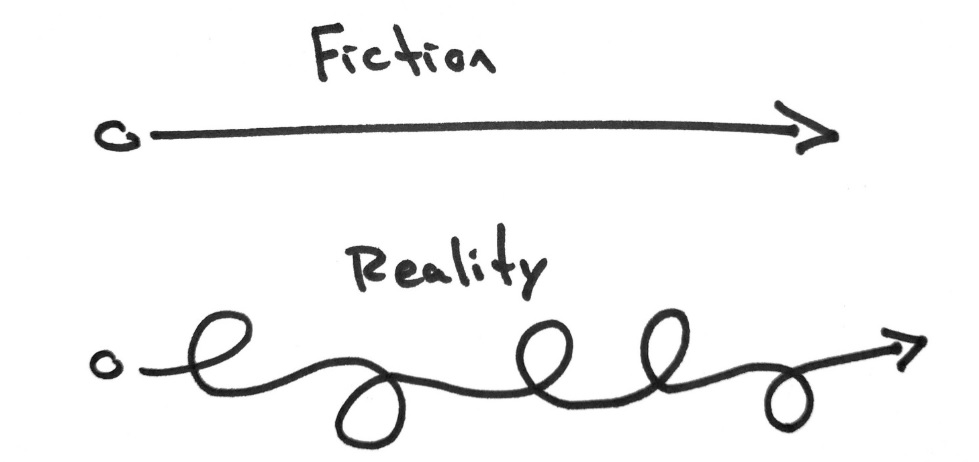

My ability to shift gears, change direction, fluctuate, and adapt is a great skill set for an educator. On the other hand, it’s not so great for mastering any of the things I’ve ever been interested in doing. I was a swimmer for seven years, but quit the sport as soon as my favorite stroke (breaststroke) changed to something akin to my least favorite stroke (butterfly). I was a climber for most of my 20s, as well as a mountain biker, skier, and snowboarder. I was competent enough to enjoy myself, but how did I expect to achieve mastery at anything if I wasn’t willing to commit 10,000 hours to it? What I realized after a year of crisis schooling (both as a teacher and a parent, as an administrator and a practitioner), is that progress doesn’t always look like progress. We may be working toward mastery at something that transcends the thing itself. There is a reason why people use the phrase “one step forward and two steps back.” Sometimes it’s necessary to take a step back to see where you are going. Maybe it makes sense to step back, then sideways, before charging ahead on a slightly altered trajectory. My students demonstrated this magnificently last year: their scores from their diagnostic assessments at the beginning of the year improved midyear, then plummeted at the end of the year. Despite working on the same skills all year long, they could not apply them consistently at the end of the year. As the light at the end of the Covid-19 tunnel came clearer and clearer into view, my students couldn’t have cared less about demonstrating their ability to integrate quotations. I don’t see this as a failure on my part or theirs; I see it simply as part of the process.

This is the problem with holding ourselves (and our students) accountable to external criteria, to following scripts others have written rather than writing our own: individual progress is different for everyone, because everyone’s goals are slightly different. If we are told (and believe) only one way from Point A to Point B exists (in fact, if only Point A and Point B exist), we might never wander off and discover Point C. In committing ourselves to only one thing, we may miss mastering the skills we really need to achieve our own success in our lives. Perhaps diversifying our interests, talents, hobbies, and achievements is the true key to recognizing what it is we are, in fact, working toward.

Of course, when we go off-script we are not always lauded for our originality; instead, we speak in terms of success and failure: a student who has decided that college was not the right choice after all is described as having “dropped out.” A couple who chooses to go their separate ways has a “failed marriage.” A woman who doesn’t want children is an anomaly rather than a prototype. A financially successful unmarried man over 30 must be “damaged goods.”

At my age, almost as many of my friends are divorced as still married. I’ve watched most of them struggle to “get back out there,” to find someone to “settle down with,” many of them in vain. The only acceptable reason for the end of a marriage is that things didn’t work out between two people, rather than one (or both) realized that marriage wasn’t the end goal. I’ve listened and played armchair psychologist to many friends who worry and wonder whether they will “be alone forever,” as if being uncoupled must mean being alone. It makes me wonder why, in seeking to change their own narratives, they have refused to change the narrative: that we grow up, leave home, get married, have kids, retire at 65 (if we’re lucky), and live out the rest of our days as content empty-nesters.

Of course, I say this having gotten divorced and then adding on to my family with a new partner and child. It’s easy for me to say we only found each other because we’d stopped looking for someone to make a complete whole out of each of our halves, and is much harder to explain to someone how I learned to see myself as a complete whole in and of itself. It’s easy to admit to others how much I hesitated to commit myself to someone else (two someones!) when our wedding is only three weeks away. It’s easy to talk about breaking free of the narrative when you’ve already written your happily-ever-after. And yet, it’s important to remember how hard it is for each of us to choose our own adventure. When I used to read this kind of book as a kid, I always read both choices before making my final decision on which way I’d experience the story. So for me, mastery isn’t about keeping my eyes and feet pointed forward and never looking back. Mastery is about enjoying the process and letting it take me where I need (or want) to go. Mastery is a moving target that if I’m lucky, I’ll never hit on the bullseye.